This year Cork All-Star Colm O’Neill confirmed his third cruciate injury, once again fuelling the public interest in this severe injury. In the English Premier League, cruciate injuries continue to make headlines with players such as Martin Kelly, Andy Johnson and more recently Sandro Ranieri all undergoing cruciate reconstruction surgery this season.

No other injury garners more media attention, with high profile players side-lined for at least 6-9 months. It is a huge blow for the athlete, eliminating them for the season, and is often associated with negative psychological responses of anxiety, fear and sometimes depression.

Cruciate injuries are more common in sports that involve high speed, sudden, rotational movements. Recently there have been claims of a “cruciate curse” and reports of an epidemic of this injury in the GAA. It might be more helpful to athletes and coaches if we can sort fact from fiction and have a look at; why this injury occurs, who is most is risk, who is most at risk of re-injury and if there is anything we can do to help prevent this injury occurring. We will also make a comparison across certain sports where the incidence of cruciate injury is higher than in the general population.

What exactly is the cruciate?

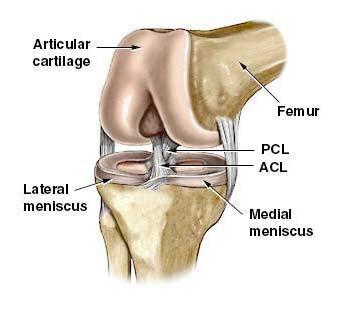

We actually have two cruciates, in both knees; the ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) and the PCL (Posterior Cruciate Ligament). An ACL injury is the one we hear all about, as injury of the PCL is generally managed without surgery, just rehab exercises. These ligaments give your knee its integral stability, with your ACL stopping your shin bone moving forward on your thigh bone. Below is a picture of a flexed right knee with the kneecap removed. You can see the ACL lying in front of the PCL like a cross, hence the term cruciate.

Historically it was a career ending injury but due to surgical advances, the ACL can now be reconstructed, giving athletes the opportunity to return to sport after surgery and a lengthy rehab which varies from 6-12 months.

How is the ACL injured?

50% of ACL injuries are non-contact, in a knee-in toe-out position, with your body pivoting above it, and the knee buckling inward. The force generated through the knee joint becomes too much for the ACL ligament to withstand and it ruptures. Michael Owen demonstrates it classically in the video below…

https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/NyI_gXOE2bw In sports such as American Football and Rugby however, the more common mechanism of injury of the ACL is through direct contact in a tackling situation. ACL injury can also occur when the knee is forcefully extended or on sudden deceleration.

Does every ACL injury require surgery?

Those with a partial tear of ACL i.e. a minor degree of ligament injury, and no functional instability can sometimes continue to play but may possibly require surgery down the line.

For those with a full ACL tear and an ambition to return to field sports, surgery is generally your best option. With surgery you are at a greater risk of early onset osteoarthritis, but this is somewhat dependent on amount of meniscal and articular cartilage damage in the initial injury.

Who is most at risk of ACL injury?

ACL injuries are more common in sports that involve high speed, sudden, rotational movements. Sports with a higher risk of ACL injury include Soccer, American Football, Basketball, Rugby, Aussie Rules, GAA, and Skiing.

Female athletes are 2-8 times more likely to have an ACL injury, argued to be related to;

- 1) Landing strategies that place greater load through their knees

i.e. landing with a more upright posture, less knee flexion, greater quad to hamstring ratio, and increased knee-in position

- 2) A larger angle from the hip to the knee

- 3) Hormonal changes that can decrease the inherent strength of ACL

- 4) Smaller anatomical attachment for the ACL

Athletes with a reconstructed ACL (those who have had ACL surgery) are at a much greater risk of ACL injury, on both the operated and non-operated knee, than those without a history of ACL injury. Up to 25 % of athletes with reconstructed ACLs go on to have a second ACL injury within 6 years.

Gaelic football shares numerous similarities with Aussie Rules which allow for some comparison with their injury data. A large study on Aussie Rules footballers over 8 seasons found the past ACL reconstruction was the strongest predictor of another ACL injury. Within the first 12 months post ACL reconstruction, their athletes were at a 10 fold increased risk of ACL injury. Beyond 12 months they were still at a 4 fold increased risk, in both their operated and non-operated knees.

Can we predict who is most likely to get a second ACL injury?

A second ACL injury seems to be strongly related to individual biomechanical abnormalities and movement asymmetries. This means how well you co-ordinate and control your movement as you jump, hop and land. One study found that compensatory strategies in the opposite hip, on landing, were the primary predictor of risk in athletes who went on to develop a second ACL injury. Recent research has also provided us with four measures to help predict who is most likely to re-injure their reconstructed ACL.

The American Journal of Sports Medicine looked at predictors of failure rate after ACL reconstruction in 206 subjects over 2 years. There was a 13% graft failure rate with a higher rate of failure in those of; younger age 19-25, earlier return to sport (222 Vs 267 days), higher BMI and return to high risk sports.

We don’t have enough baseline data on re-rupture rate in GAA but across other sports ACL re-injury rate appears to be equal, suggesting that a second ACL injury may be more individually specific than sport specific.

Does the type of graft used affect re-rupture rate?

There is no difference in terms of ACL re-injury rate of hamstring vs patellar tendon graft. However, there is a difference between autograft (graft from your own body) Vs allograft (donor graft), with a higher rate of failure in those younger than 20 years who receive an allograft.

Is it possible to decrease your risk of ACL injury?

Yes. There is mounting evidence that those partaking high risk sports can decrease their risk of ACL injury, by regularly completing a series of warm-up programmes that encourage neuromuscular training and balance activities. FIFA and Women’s soccer associations have led the way in ACL prevention programs. Ideally we need to be able to identify those most at risk of injury and then target prevention programs at these athletes.

Do blades on your boots increase your risk of ACL injury?

There is conflicting evidence in relation to blades versus studs and associated injury risk. Blades were originally designed to offer more stability to the support foot in kicking in soccer, made famous in the mid-90s by a certain David Beckham. Due to their claims and some evidence of them giving more grip on the playing surface it has been argued that they can contribute to injuries.

A study on 15 professional soccer players comparing two types of both studded and blade soccer boots found no significant difference on knee loading. Increased knee loading forces have been indicated as a risk factor for knee and ACL injuries.

There is one study that looked at numerous top level European soccer surfaces and found that blades were associated with significantly higher rotational torques than studs, on natural grass only. Authors reported the studs were “probably safer” however these results must be interpreted with caution as it was a laboratory study, showing blades were associated with higher torque values but no correlation was made with injury prevalence.

Does the playing surface or weather conditions affect your risk of ACL injury?

Research, again from Aussie Rules injury database has found a significant increase in ACL injury rate in weather conditions associated with a drier playing surface; specifically a higher water evaporation rate and lower rainfall. However this research finding might not have as much applicability to Irish weather and GAA pitches…

It gets a bit more complicated and speculative when we look at pitch surfaces and artificial versus natural grass. Specific to ACL injuries, a study on natural grass surfaces in Australia found fewer ACL injuries on Rye grass surfaces compared to Bermuda grass surfaces.

Increased rotational torque has been identified as a small possible risk factor for lower limb injury but not specifically for ACL injury. A study on football turf used for top-level European soccer showed that football turf without infill showed significantly lower frictional torques than natural grass, whereas football turf with sand or rubber infill had significantly higher torques. But again, this was laboratory testing only and not specific to injury incidence, just related to one of the factors that is sometimes associated with lower limb injury. Clear as mud.

ACL injuries per sport

Below is a table which compares the percentage of ACL injuries in a given sport relative to all injuries in that sport. There are many issues with comparing sports injury data; however it does give us an indication of ACL injuries compared to all other injuries in that sport. Ideally we would like to compare injury incidence per 1000 player-hours, separated across match and training hours but as of yet that data is lacking.

| Table 1. ACL injuries as a percentage of all injuries in a given sport | |

| Female Gymnastics | 4.9% |

| Female Basketball | 4.9% |

| Female Soccer | 3.9% |

| American Football | 3-3.5% |

| Aussie Rules | 2% |

| GAA (male only) | 1.5% |

| Men’s Basketball | 1.4% |

| Men’s Soccer | 1.3% |

| Rubgy | 0.5% |

As discussed, ACL injury is not unique to the GAA. If you play a sport that involves high speed, sudden, rotational movements, then yes, you are at a higher risk of ACL injury than the general population. However, the risk of ACL injury should not be seen as a deterrent for sports participation as the benefits of sport far outweigh the risks!

Please do not hesitate to contact us if you would like more information or advice on this topic.

Michelle Biggins

Chartered Physiotherapist

085-1670574

charteredphysio@gmail.com